|

Contributed Graphic

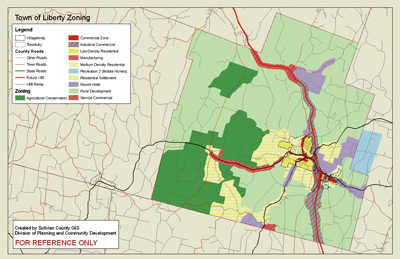

The light green and dark green areas in the map above will be affected by a moratorium

|

Moratorium Sparks Debate in Liberty Major Subdivision Development Plan

By Dan Hust

LIBERTY — November 24, 2006 — The Town of Liberty continued to be ground zero on Monday for the countywide discussion on growth and development.

In a two-hour public hearing on a proposed major subdivision moratorium law, the Liberty Town Board got an earful from residents, developers and area officials regarding the region’s next step into a period bustling with projects.

The moratorium, if enacted, would ban construction for six months on any major subdivision (5 or more lots) in the AC (Agricultural Conservation) and RD (Rural Development) zones, which together comprise more than 50 percent of the township’s land area.

Projects already being considered by the township prior to August 22 would not be affected by the proposed law, said the board, nor would proposals pending within the Village of Liberty.

The moratorium could be extended for two more three-month periods, thus possibly lasting up to a year, but Supervisor Frank DeMayo said a decision would not be made until at least January.

In the meantime, town officials said they’re reviewing zoning laws from Goshen, Fishkill and New Paltz.

“Very soon we hopefully will be able to enact some laws that deal with these issues,” DeMayo said.

Regardless, speakers divided themselves into three camps on Monday, although at times their ideas overlapped.

Those for the Moratorium

Support of the moratorium proved to be a minority viewpoint that evening, but it was a viewpoint nevertheless passionately argued.

“We need a moratorium to plan for quality development for our town,” said White Sulphur Springs resident Peter Stettner. “We do not have the water or sewer capacity in place or planned for the kind of development coming to the town.”

“This is a rather narrow, well-tailored moratorium,” added Liberty attorney Ron Litchman, saying its purpose was to preserve the town’s ability to change its own laws without pressure.

“Once it becomes known that a town is considering a moratorium,” he pointed out, “there is a rush to submit and approve projects.”

He felt fears that a moratorium would scare away developers were unsubstantiated, arguing that Lake Tahoe in California once had a moratorium and did not noticeably suffer.

Claiming that at least 10 percent of Liberty’s agricultural zone was already targeted for major development, he urged the board to extend the moratorium to encompass all development, rather than post-August 22 alone.

“We want a plan that’s right for here, for us,” he said.

“I just want it done right,” agreed 55-year Liberty resident John Lennon. “I’m not looking to chase developers away.

“The people here who are really most afraid [of the moratorium] are our developers,” he observed. “…But they’ll come back. They’re not going to run away.”

Time is what is needed, said all three men.

“We have to sit and think,” Stettner remarked. “What the heck is so wrong with that?”

Those in the Middle

People like Caroline Sklenar of Liberty had already thought about the issue and come away uncertain.

“I don’t know what to do here,” she remarked to the board.

“I’m torn on this,” said White Sulphur Springs resident Gayle Marshall.

On the one hand, she explained, “I really find the planning board is not asking the right questions” of developers – and she urged the town board to require critical questions be asked and answered.

On the other hand, “I’m not sure I can be for a moratorium financially” if the day comes to sell property.

Those Against the Moratorium

By far the largest group of speakers Monday opposed the moratorium, but not all for the same reasons.

Lou Feder, a longtime Liberty visitor and New Jersey town planning board member who has worked for a developer, said his township went through a similar growth spurt a decade ago but avoided a moratorium.

“Moratoriums are done usually in desperation or when it is thought there are no alternatives,” he remarked. “I think moratoriums never work – they scare the very people you need to help this town into the next town.”

While he acknowledged townships often have “love-hate relationships” with developers, officials’ attitude should rather be “we’re here, we want you and we want you to build in a certain fashion.”

“Make the laws as tough as you want them to be,” he added, “because developers don’t care about that.”

Feder said what developers do care about is being in a growing town – because that’s good for business.

And not just for developers. Residents urged the town board not to create a bad reputation regarding growth, as that could harm local contractors’ ability to find employment.

One of Liberty’s residents is a developer who uses those contractors: David Goodstein, a former planning board member himself.

“Moratoriums send out a message that’s really scary,” said Goodstein, owner of Brookside Homes and builder of hundreds of houses in the township. “It’s always about fear. Are we afraid of people?”

Goodstein postulated that the fear is related to NIMBYism – Not In My BackYard.

“My fear,” he countered, “is that there aren’t going to be people here to support the businesses that will open… People make things better.”

Jay Zeiger, an attorney speaking on behalf of unnamed clients, argued that no compelling reason had been established for creating a moratorium.

“A moratorium just prevents people from doing business,” he said.

Like others who spoke against the moratorium, he urged the town board to amend laws to guide development in an open process where business is allowed to flourish.

“You can upgrade zoning laws without a moratorium,” agreed Allen Werlau, a builder and developer who serves on Bethel’s Zoning Board of Appeals.

Werlau also criticized the minimum number of lots, saying five was too low a figure to be considered a “major subdivision.”

Continuing the theme, developer Jerry Gorelick told the board, “A moratorium isn’t the purpose of what you want to do – it turns people away. You want to stiffen your laws.”

Cindy Karras of Swan Lake, who has been fighting a local developer over various environmental issues, couldn’t agree more.

“I am in favor of fixing a system gone terribly wrong,” she said, detailing how she had to spend a great deal of money to get the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to do its job of monitoring development and enforcing related rules.

“Somebody has to protect what’s ours now,” she concluded. “It’s not working right now.”

Friend and fellow Swan Lake resident Cora Edwards offered a series of solutions in the form of three proposed resolutions.

1. An applicant’s plan for any well and septic system (individual or multi-residential) must be certified by a professional engineer.

2. Application fees for subdivisions greater than three/four lots must pay money into a fund for a third-party review subject to a public comment period prior to approval.

3. Permits should be issued for five years and renewed only after an inspection (for which the applicant pays) with results made public.

Edwards and several fellow Swan Lake and White Sulphur Springs residents took the view that while a moratorium isn’t the answer to Liberty’s concerns, neither is the current situation, where up to 2,000 housing units have been proposed in the past few months.

“We’re concerned #1 about infrastructure… but we’re also concerned about the shape and form of how Liberty’s going to change,” explained Swan Lake’s Bill Liblick.

Saying he wasn’t racist but didn’t find a Kiryas Joel-type situation ideal, Liblick added, “The people who are buying in Sullivan County are a sect of Hasidim, and it’s fearful for people in Sullivan County.”

But Jean Pasternak, a real estate broker who deals in Liberty properties, felt there’s an offensive undercurrent to residents’ concerns.

“There is a sense to me here of xenophobia,” the New York City native remarked.

Turning practical, she continued, “We are not an agricultural district anymore. This is not the Lake District in England… We need to make money, and we should be embracing other people.

“We are a depressed county,” Pasternak added, saying the tax base desperately needs to grow. “I pay $10,000 in taxes for two tiny houses [in the Village of Liberty], and I see no amenities.”

However, Sullivan County Partnership for Economic Development Executive Director Marc Baez, a Liberty native, urged residents to look beyond just their homes.

“A moratorium has a significant impact not only on the residential side but on the commercial side,” he explained. “We’ve got to make the case that we’re open for business.”

Saying he couldn’t buy a “decent white shirt” in the area, Baez urged officials to be sensitive to developers’ concerns even while enacting tougher laws to guide growth.

“A moratorium… is a death knell for growth and development in your area,” he warned.

Rockland and Fremont town engineer Wes Illing said it can have ill effects on relations within the township, as well.

“A moratorium really gets everyone all excited,” he remarked. “It polarizes a community.”

He urged board members to focus on zoning loopholes, especially those relating to stormwater runoff, rather than a moratorium.

As Parksville resident Solly Kleinberger put it, “You don’t need to use a body cast to repair a broken finger.”

|