Retrospect Column by John Conway

March 15, 2013 — In late February, 1951, the basketball team from the City College of New York was returning home on the train from Philadelphia where they had just trounced the Temple University squad.

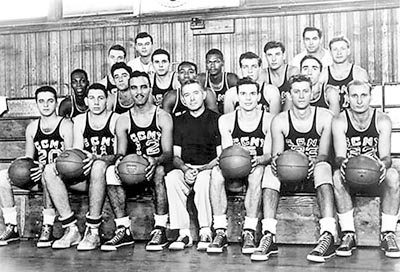

The year before, the Lavender and Black had been hailed as one of the greatest college basketball teams of all time, having won both of college basketball’s biggest post season tournaments, the NCAA and the NIT, the only time that feat has ever been accomplished. The talented team had stumbled somewhat during the current season, losing to several teams it had been expected to beat, but was seemingly hitting its stride just as the tournaments were about to begin.

As the train approached New Brunswick, New Jersey, a man summoned the team’s coach, the legendary Nat Holman, to a private car. “I’ve got some bad news for you, Coach,” the man said. “I’ve got orders to pick up some of your boys.”

The man was from the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, and before he and his colleagues were through, college basketball, Madison Square Garden, and the Sullivan County resort industry would all be dragged through the mud, and none of the three would ever be the same.

The investigation eventually revealed that points were being shaved in college basketball – that is players were conspiring to win games by fewer points than their teams were favored by – at least as far back as 1949. It hit the big time in the summer of 1950, when a major gambler, Salvatore Sollazzo, and Eddie Gard, a former college player who had shaved points in the past, met at Grossinger’s.

Soon, it seemed as if everybody wanted to get in on the fix, and the scandal would eventually involve 32 players from seven colleges fixing 86 games in 23 cities in 17 states. And when it was all over no one was quite sure that all the guilty parties had been caught.

Overconfident gamblers were careless gamblers, and they contacted the wrong player when they approached Junius Kellogg, the center on the Manhattan College team. Kellogg reported the bribe offer to the Manhattan D.A.’s office, and a trap was sprung for the gamblers. The full-blown investigation followed.

Despite the contentions of some of the nation’s finest coaches, it would be inaccurate to blame the point shaving scheme entirely on the atmosphere that existed at the Catskills’ resorts, or on the college ballplayers who spent their summers working – and playing – there. But it is undeniable that the resort atmosphere played some role in the scandal. Once the whistle was blown, the outcry was loud and clear. The Catskill resorts were the culprits, many said, keep the ballplayers away.

Calling the hotel teams “schools of crime,” CCNY coach Nat Holman forbid his players to play in the Catskills. Kansas coach Forrest “Phog” Allen, a basketball institution, was among those to yell the loudest.

“In the east, the boys, particularly those who participate in the resort hotel leagues during the summer months, are thrown into an environment which cannot help but breed the evil which more and more is coming to light,” Allen claimed.

Of course, it was revealed a short time later that the point shaving had not been confined to “the east” but also involved Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, which had actually thrown a game to Allen’s Kansas team the year before, as well as perennial powerhouse Kentucky, which had been particularly active in shaving points, despite its revered coach Adolph Rupp’s claim that the gamblers couldn’t touch his players “with a ten foot pole.”

So shortly after it had reached its heyday, the Borscht basketball circuit was discontinued. One Catskill veteran, interviewed by author Stefan Kanfer for his book, “A Summer World,” said that after the scandals, “the gyms were quiet. The big sport was Simon Says. For entertainment we went back to singers and dancers and stand-up comics.”

It was nearly impossible for the hotels to fill the void left by the absence of basketball. In the spring of 1953, Jack Barsky, the owner of the Flagler Hotel in Fallsburg, wrote a letter to Maurice Podoloff, then the commissioner of the National Basketball Association, asking him to allow professional players to moonlight in the Catskills for the summer.

Barsky’s plan did not include individual hotel teams playing against one another, but two teams made up of NBA stars touring the Catskills for a series of night time exhibition games.

The Liberty Register newspaper reported that Barsky promised that “no hotel guest would be charged admission,” but that a flat guarantee would be arranged for the players and the league to divide up.

“Barsky, who has both indoor and outdoor courts at the Flagler, said he would be willing to hold the first basketball game as a trial and predicted that other hotels would soon ask for games,” the Register reported.

Barsky wrote that basketball “was always one of the most popular sports in the Catskill resort area and a program of professional games throughout the summer would be a tremendous boom to the sport. There are upwards of two million potential customers in the Catskill area and those that are exposed to professional basketball for the first time would become steady customers when league play begins.”

The NBA was in its infancy in 1953, and it needed all the exposure it could muster, but despite the obvious appeal of this proposal, and the pleas from other hotel owners who felt that the arrangement could benefit both Sullivan County and the league, the NBA refused to change its rules and the plan to form a summer barnstorming circuit never materialized.

John Conway is the Sullivan County Historian. This is the second and final part of a series on the summer basketball scandals that involved Sullivan County resorts in the early 1950s. He can be contacted by email at jconway52@hotmail.com.